Ava DuVernay’s Unconventional Ways

Cinematic Justice: The PS Interview With Ava DuVernay

Ava DuVernay (Photo: Danielle Levitt)

It’s a fine May day in Louisiana, with chalk clouds scuttling across an opal sky. I’m an hour west of New Orleans, driving along old River Road and following the lazy Mississippi. I pass several plantations that were tilled by black slaves, their dilapidated cabins still standing in the fields. Although it’s 84 degrees today, a chill passes through me. I come upon a museum dedicated exclusively to black slavery, where visitors can view life-sized statues of slave children and tiny iron shackles. The air is thick with ghosts and recrimination.

My destination, St. Joseph Plantation is hard to miss. A Creole-style manor spreads like a 12,000-square- foot hoop skirt across an upper lawn. Below, a dirt lot is packed with a dozen 40-foot-long tractor-trailers and 100 or so cars. Workers mill around a giant white frame tent; several honey wagons serve as restrooms, and a huge generator hums like a thousand insects. We’re on the set of Queen Sugar, the first television drama from the acclaimed writer, director, and executive producer Ava DuVernay.

DuVernay’s career is full of firsts. She is the first African-American woman to win the Best Director Award at the prestigious Sundance Film Festival (2012), the first black American female director to be nominated for a Golden Globe Award (2015), and the first black female director to have a film nominated for Best Motion Picture at the Academy Awards (2015). In addition, the 44-year-old is a high-profile activist and the founder of ARRAY, a film collective that helps other women and people of color distribute their films.

DuVernay’s career is full of firsts. She is the first African-American woman to win the Best Director Award at the prestigious Sundance Film Festival (2012), the first black American female director to be nominated for a Golden Globe Award (2015), and the first black female director to have a film nominated for Best Motion Picture at the Academy Awards (2015). In addition, the 44-year-old is a high-profile activist and the founder of ARRAY, a film collective that helps other women and people of color distribute their films.

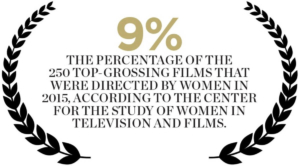

Queen Sugar, which premiered in early September on the Oprah Winfrey Network, marks yet another milestone, because DuVernay, as executive producer, hired an overwhelmingly diverse cast and crew and only female directors for the 13-part TV series. You wouldn’t think it’d take nearly a century for progressive Hollywood to make these kinds of advances. But it has.

DuVernay embraces her role as a changemaker. With long, braided locks, kohl-rimmed eyes, and ruby- painted lips, she’s a stylish presence, but also eminently practical, wearing jeans, a light hoodie, and canvas shoes for tromping through the sugarcane fields. Toward the end of the day, we sat down together on the porch of a 170-year-old slave cabin and discussed her projects, her activism, and her plans for the future.

You’ve done films about our prison system, the civil rights movement, and the devastation of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. How does Queen Sugar build on the issues you’ve addressed in these works?

With this project, I’m getting into issues of representation and misrepresentation. When you think about the cinematic injustice that’s been done to people of color and women since the dawn of the medium—look at a film like Birth of a Nation of 1915 [D.W. Griffith’s racist epic] and the ways that images are used to disparage and misrepresent the humanity of people. I feel very activist in creating an image of a whole-bodied character, with complexities and frailties and triumphs and tragedies, in the body of a woman or a person of color. To me, there is justice in the very rendering of that image. To present a black family that is not a caricature, but is very fully drawn in their humanity, is radical, unfortunately.

I think, oftentimes, for people who live in a place of privilege, it’s a challenge to strip away the notion of justice to the very simple idea that this life matters just like any other life. That’s what the Black Lives Matter movement is about. It’s a very core truth, and so much of what we are doing here as women filmmakers is to try to portray that truth cinematically.

We have a formerly incarcerated individual as one of our main characters, and we try to really pull back the veil on him in terms of what the lives of formerly incarcerated people and their families are like. There’s a journalist who writes about social-justice issues in the show, and she’s following a case about plea bargaining, and pulling back the veil on the really, really unjust systemic patterns around plea bargains and people of color, people from low economic backgrounds. But all of that is secondary to the complete rendering of black people. That for me is the biggest political statement if there is one.

I heard that you showed a rough cut of the film last night to the actors, and it was very emotional. Some of them even broke down crying. Why do you think that happened?

I think it goes back to the answer before. You have black actors watching images of black characters fully rendered. Not shadows of themselves, not caricatures, but fully rendered human beings with shades of dark and light, sinister, sincere, sympathetic, sociopathic—all of the things that we are as human beings. To see that presented in a way that is meaningful and purposeful and intentional—that is what the whole thing is about. The characters are not tangential to someone else’s main action. They are the center.

I think it was emotional for the actors to take that in. And, also, it’s a little shocking that those kinds of characterizations are so rare.

Ava DuVernay with Oprah Winfrey. (Photo: OWN/ARRAY)

The Queen Sugar crew is a varied group of around 125 men and women—young and old, Latinos, blacks, whites, and Asian Americans. During my visit many seemed aware of the importance of this production. One of the directors, Neema Barnette, walked around the set smiling all day. The first black woman to direct a sitcom and the first to land a three-picture studio deal, she said to me, with a faintly incredulous look on her face, “Who does this, hiring all women?” She lowered her voice and added: “I thought I’d never live to see this day.”

Even though blacks and other ethnic minorities make up 40 percent of the United States population, America’s stories are still told overwhelmingly by straight white men. DuVernay is dedicated to changing this. She believes that we cannot create a healthy and equitable society if the experiences of more than half of all Americans are excluded from the country’s most popular form of entertainment, the $130 billion film and TV industry.

I’ve heard about other producers, such as Ryan Murphy (American Horror Story) and J.J. Abrams (Lost, Roadies), who have pledged to double the number of women on their staffs, or more. Do you think that will happen?

I think it’s going to take men who are feminists and who are in positions of power to say: “There’s more than my point of view. Let’s bring in a Latino, a Native, an Asian American, a Pacific Islander, or a black.” They’re going to have to bend a little to open the power base. But, like any effort, it’s going to take folks on all sides.

There is definitely a change afoot. I hope it’s not just a trend. It’s been talked about for years, the fact that this industry is mostly men. Now people are being called on the carpet. Now you are going to raise some eyebrows if you are producing 13 episodes of a TV series and there is not one woman director. That’s 50 percent of the population that you are basically ignoring—purposefully. It has to be on purpose. It’s not like female directors don’t exist. They are here, they are ready and willing and want to do the work. So, that’s discriminatory.

So why is that important? How does having more female and Latino directors change national policy or create better laws?

For me, the image is supreme over music or other kinds of art. When you close your eyes, when you dream, when I look at you, I see an image that I then process. It helps me behave in the world and in the moment. So if the images that are constructed and projected and amplified in society don’t include certain places and situations—if some people are absent—that affects future generations. If some people are rendered as caricatures or as less than human, that has a big effect. So, yes, I think it impacts policy and politics, culture. And you know, it’s just vital that we get that part right.

Where does this deep sense of justice in you come from?

Maybe from my aunt Denise, who was a nurse, and who really, in my early years, introduced me to the idea. When I think back to the first time when I felt any kind of activist leaning, it was with my aunt Denise taking me to an Amnesty International concert. I saw U2 perform. It was one of my first concerts, and the music and the meaning behind the songs—to be able to see art and music converge. I remember I had my little Amnesty sticker, and I joined, and I thought: “Wow. You can do something about things that aren’t right,” you know?

I still have the souvenir book that Amnesty gave out. That’s funny that I remember that show. It had a big effect on me.

So your aunt was an activist?

Yeah. Just in the ways that some people are. True activism shows itself not necessarily through the artists or the leaders with the microphone. Nothing can be done if you don’t have the nurse who takes her niece to the thing, you know what I mean? Nothing can be done if you don’t have the people who walk with and behind King. Nothing can be done if everyone doesn’t rally around Black Lives Matter or Occupy Wall Street or immigrant rights. You need that mass. You can’t dismiss the importance of the crowd, of the unsung heroes, of everyone who helps to move the needle.

And now, you raise funds for the residents of Flint, Michigan; raise awareness about post- Hurricane Katrina problems; and agitate for #BlackLivesMatter and #OscarsSoWhite. How do you balance your art and activism?

I do the things that are important or that resonate with me. Flint resonated with me. For whatever reason the idea of folks not having water emotionally resonated for me to the point that I wanted to do something. Issues of incarceration and mass criminalization really move me. I’m just finishing a documentary that I’ve been working on quietly for a while. After Selma, Netflix came to me and very generously asked what I might be interested in doing. They are like-minded people, and I said: “You know what? I want to make a doc. I want to do a definitive overview of the prison system and how we got here.” So they gave me a nice chunk of change and we went off with our indie crew and tried to tell the story. We interviewed Bryan Stevenson, we interviewed Michelle Alexander. We interviewed everyone from Angela Davis to Newt Gingrich to try to deconstruct it and to really make clear that prison is not a place where bad people go, which is what most Americans think. It’s this really insidious, unjust system that has been built over many generations, but something can be done about it.

And you use Twitter a lot.

Yeah. Today I was trying to get some eyes on this New York Times op-ed about the language of incarceration—how when we call someone a felon it’s really branding them as second-class citizens. They’ve done their time. Why do we call them ex-cons? They were punished for whatever they did, rightly or wrongly. Now they should be free of the stigma and the box-checking. It’s something that I care about. I love having social media as a way to amplify things. I don’t have to have an interview; I can just point to something that means something to me.

On set, DuVernay was like the eye of a hurricane, calm in the midst of intense forces. Sometimes during our conversation, she’d talk and gesticulate with such emotion that her tiny braids would dance around her shoulders. You get the sense that DuVernay is not only passionate about things that mean a lot to her, but has had to defend her passions and positions repeatedly. Take Selma, for example.

In making that film, DuVernay was the outsider who told the story of the civil-rights era through the eyes of the black men and women who marched with Martin Luther King Jr. It was the first major film about King, and, when it premiered in 2014, critics forecast that DuVernay would get an Oscar nomination, potentially doubling the number of female Best Director winners from one to two (Kathryn Bigelow for The Hurt Locker being the first).

But not everyone was impressed. Director Quentin Tarantino condescendingly said that DuVernay “did a really good job in Selma, but Selma deserved an Emmy,” implying it was better suited for TV than the big screen. Harsher still was a Washington Post op-ed penned by Joseph Califano Jr., a former aide to President Lyndon B. Johnson, who claimed that Johnson, not King, came up with the idea of a march on Selma. Never mind that the distinguished historian Taylor Branch has pointed out that King purposely kept his plans for Selma from LBJ, “knowing that Johnson would not welcome his tactics of street protest.” The campaign to discredit the black female director had begun. And it continues.

This morning, a New York Times reporter sent me a quote by the director of this new lm about LBJ [Robert Schenkkan, All the Way], and in the quote, which is about me, he says, “She’s a very talented filmmaker, she did a great job with King and Coretta, but her portrayal of LBJ was unfair because she portrayed him as someone who didn’t care about civil rights and I don’t believe any historian would agree with that.” This gets into the issue of truth and fact and perception because this white male director’s perception of the facts of LBJ’s presidency—and I put “facts” in air quotes—is perceived by him from a place of privilege. It’s perceived by me as the granddaughter of a civil-rights marcher. Yet he and folks in power who hold a similar view can disparage my perception and my comprehension of the quote-unquote facts, and call them lies, and not truths because our perceptions are not the same. I’ve come up against this quite a bit.

Do you think it’s because you’re a woman?

I attribute it more to being black. I don’t think people lack comprehension. I don’t think people lack an understanding. But they lack an embracing of our differences. They want everyone to line up behind one way of thinking, which I’m not going to do.

You’re not going to ask permission.

No. But I think it’s interesting that a different perspective is seen as a lie, not a truth, and I think that rhetoric can get you into a really dangerous place.

I welcome people. I encourage people to see that man’s film. I encourage people to see my film. I encourage people to see any artist’s rendering of whatever and to investigate it and study it for yourself and see what you think about it, because that’s all that really matters in the end. What you think about it doesn’t have to be the same as what I think about it. I won’t think less of you because you think differently about it.

I welcome people. I encourage people to see that man’s film. I encourage people to see my film. I encourage people to see any artist’s rendering of whatever and to investigate it and study it for yourself and see what you think about it, because that’s all that really matters in the end. What you think about it doesn’t have to be the same as what I think about it. I won’t think less of you because you think differently about it.

I sensed a change in you after Selma was locked out of Oscar contention in yet another all-white Best Director category, and you skipped the awards to attend a fundraiser you’d helped to organize for the people of Flint. Prior to that, you seemed really focused on getting your films completed in order to make a certain festival or award deadline. What was it like promoting Selma, given all the pressure and hype?

I used to be a publicist in the film industry, so I knew what the awards season was. That wasn’t what I was chasing so much as bandwidth. I want my films to be seen. I want them to be distributed. I want them to be at the festival. I’ve seen so many beautiful black films sit in people’s drawers, not being seen, not being talked about, not moving the needle, not doing anything. I just didn’t want that. My singular thought was, “I won’t allow my films not to be seen, considered, or amplified, even if I have to do it in a different way.”

You know, I still struggle with awards, because I don’t really have a grasp on how I should feel about it. I’m not ambivalent, but when I walk a red carpet, it doesn’t do for me what it does for some of my colleagues, because, as a publicist, I used to get down on my hands and knees and roll out the red carpet. I know how all those photographers who are screaming your name got there. Someone had to call them, pitch them, write the media alert, send the media alert, check them in. So, unfortunately, a little bit of that shimmer doesn’t shine as brightly for me as it does for others.

I think in the Selma time, I found myself getting caught up in it. Part of the work is to amplify the work, but you can get caught up in it—like a hamster wheel. I think there’s a point where the amplification stops and the glorification begins so hardcore that it’s not healthy. It’s certainly not healthy when you’re an outsider, and just the whole #OscarsSoWhite thing. All I can say is I’m just over it. You know what I mean?

Now that you’ve started working with major studios on high-stakes projects, is it harder for you to keep your vision and voice?

It’s definitely been challenging to be talking with big companies about projects when there’s millions of dollars or tens of millions of dollars at stake. The film I’m developing for Disney right now, A Wrinkle in Time, is a $100 million project. To try to keep one’s voice and keep what matters in play, I’ve just had to be really focused on the kind of projects and the people I want to be involved with. My intention is to be really rigorous in finding like-minded people and like-minded companies who want to tell the same kinds of stories that I do.

Not every studio and every network want to do it the same way. With Queen Sugar, it was Oprah Winfrey’s network OWN that said, “We’ll give you the freedom to tell the story the way that you think it should be told.” There were a lot of companies coming my way, but not offering that freedom. Folks said, “Oh, why go there when you could have gone here, here, or here?” Those other places weren’t saying: “Be free. We just want to hear your voice.” The studio, Warner Horizon, was very, very supportive of that as well. I was really specific that I didn’t want a pilot, so we went straight to series, which is also worth noting because there are very few companies that give women that kind of space, particularly black women. So, I’m grateful for that. I think it’s really important to name-check the people and the companies that aren’t hiring us, and the companies that are.

On the first two episodes, which I directed and wrote, there were no studio notes. There were no network notes either. It was literally going on air exactly how it came out of my brain, which is really rare in this industry. For me, it’s about hanging on to the fact that it’s possible for me to have that kind of freedom. I see many of my white male counterparts retaining their voice, so why can they do it and I can’t? Why is my voice one that should have to bend or be made smaller to fit into some kind of studio paradigm?

I also just think you have to not really care about the money portion of it. A lot of the director game is to go from a $1 million movie to $5 million, to $10 million, to $25 million, and there’s a status that goes with having made a $100 million movie. But it just doesn’t matter to me as much. It makes things easier to have more money, but there’s always something that you want to do that you can’t do. There’s always some shot you want to get and the day is not cooperating. The sun is not going to wait for you no matter how much money you have. It’s going to go down.

So I don’t chase it. And I think that has allowed me to always have a security blanket. I can say, “Let’s go make a $100,000 movie,” which I have many ideas for. One year I’m just going to make five $200,000 movies. I’ll take a crew for a year and just pound out the films. I mean, there are different ways to tell the story. The reason I love TV now, and Netflix and the collapsing windows and walls, is that my foremothers— women who directed, and the black folks who directed films before me—were really trapped in a segregated cinema. They were restricted in the kinds of films that they could make because of the tools. There was no digital; you had to shoot with a 35-millimeter. You had to get that camera, get that film, get the resources to process the film. It’s a very expensive medium.

But now, to be wrapped up in the money game when I can literally make a movie on my iPhone? It just doesn’t compute for me.

I hear you’re casting some new faces to play the three time-traveling kids in A Wrinkle in Time.

Yeah, they’ll be unknowns. My work is not based on any studio algorithm by which a certain actor is going to be hired to bring in more money. It’s based on a point-of-view and the way I want to tell this timeless story. The lovely thing about Disney and about working on a classic like this is that they are wisely saying it’s the property itself that’s the star. So it doesn’t have to have George Clooney in it, you know what I mean?

DuVernay is very deliberate with her projects and doesn’t stray far from her chosen path. She turned down the chance to direct Black Panther, a tentpole project based on the Marvel Comics character, and dropped out of a Steven Spielberg production whose timetable might have clashed with the schedule of A Wrinkle in Time. Meanwhile, she’s working on a murder mystery set in New Orleans that explores the havoc wreaked by Hurricane Katrina. And her documentary about America’s grossly unfair prison system, The 13th, opened the New York Film Festival in September, the first time a non-action film was selected for that coveted slot. Meanwhile, Oprah has been cast to play Mrs. Which in A Wrinkle in Time, Queen Sugar got picked up for a second, 16-episode season, DuVernay’s distribution firm ARRAY has inked a deal with Netflix, and there are other pet projects—far too many to discuss today.

The late afternoon sun is slanting across the porch, and I spy an assistant hovering in the background, waiting for the right time to break this up. The director and I are deep in conversation, sitting across from each other knee-to-knee in the golden light. Red-winged blackbirds dart under the branches of oak trees, embroidering the air with song. A lizard scampers across the floorboards. DuVernay doesn’t move, but clearly she is needed back on set.

One last question. After working for months on a huge production like this, how do you take care of yourself and refill the creative well?

[Throwing her head back, she laughs.] I don’t do that very well. I don’t do it very well at all. I think that’s coming more to light for me with the passing of my father [in March]. Because he didn’t live to work, he worked to live. He worked to enjoy everything outside of work, whereas my work is my life and I really enjoy it, so in some ways, I feel like, well, I’m living my dream. I’m happy. There’s no other way I’d want to be spending my day, and yet I know that I could definitely have more balance in life. So it’s something that I’m going to do as soon as I finish these next nine projects.